GGB; Glasgow, Gentrification, Bloomsbury

Growing up, my dad owned a secondhand bookshop in the Brunswick Centre in Russell Square. Early 00s, a peeling grey estate hailing over a quadrangle of eclectic shopfronts connected by broken cement paving slabs and an air of almost forgotten, the brink of survival. Not a chain in sight. Residents of the estate above mingled under clouded Tupperware skies. Brutalist architecture was yet to have a resurgence. Pre-hipster heyday. Before brutalism became fodder for the photography student’s experiments with the aesthetics of youth culture.

I used to ride an electric scooter into dipped drains to feel a hint of vertigo. Next door was a family run pizzeria. They sprinkled oregano on my takeaway pizza and I didn’t like the herby taste. There was a space dedicated to British comics, an eternal Beano window display framing the near empty space. A few doors down was a discount store where my mum bought three unergonomic suitcases. In the windows sat discoloured old fashioned teddy bears with red ribbon bow ties, stiff with un-care, on dusty glass shelves as glazed over as this memory. As a sales tactic, the owner told my sister to jump up and down. No hesitation – purple fleece and flared GAP jeans, bob flicking up and back with each tuck of the heels. They’re still around today so he wasn’t wrong. The suitcases have outlived his business, as well as that iteration of the Brunswick Centre.

I revisited the place recently. I know what’s there now, and revisiting feels like driving past the house a parent was born in. Familiar, laden with stories, a foundational building block to the architecture that becomes your identity. Now, it’s Waitrose, Pret, Oliver Bonas, Costa. Crisp white and pastels painted memories of the London I grew up in. With the same hand, this sweep knocked my childhood neighbourhood Stoke Newington. The flux of immigrant shop owners, the imperfection of an undusted corner, unflattering light transformed into the smell of Aesop hand wash. UCL students snapping 0.5 selfies backlit against Ridley Road. Clissold park cafe’s after school chicken nuggets. When the Chinese takeaway became fish and chips. They were so busy they offered my dad a job.

“Spiritually, gentrification is the removal of the dynamic mix that defines urbanity – the unfamiliar interaction of different kinds of people creating ideas together. Urbanity is what makes cities great, because the daily affirmation that people from other experiences are real makes innovative solutions and experiments possible. In this way, cities historically have produced acceptance, opportunity, and a place to create ideas contributing to freedom. Gentrification in the 70s, 80s and 90s replaced urbanity with suburban values from the 60s, 70s and 80s, so that the suburban conditioning of racial and class stratification, homogeneity of consumption, mass produced aesthetics, and familial privatisation, got restated into big buildings, attached residences, and apartments. This undermines urbanity and recreates cities as centres of obedience instead of instigators of positive change.”

– Sarah Schulman, The Gentrification of the Mind, Witness to a Lost Imagination

I went to art school in Glasgow. I spent five formative years there where I transformed greatly as a person. To understand the beauty of lo-fi art. How a simple drawing on A4 printer paper pinned precariously on a puckered wall can say as much as a Modigliani hung in ornate gold within the white cube gallery. How an anti-establishment way of thinking can open gateways to creativity, how it can be actively encouraged rather than institutionalised through oppressive systems of thought. How narrow minded and self-obsessed Londoners can be; posturing at the centre of an ambivalent universe. How all experiences, people, identities places should be understood with intersectionality. There is no binary, there is no dogma.

In my first year, the soundtrack to growth was Lorde’s Pure Heroine. Techno became a background hum as well as the lingering taste of Buckfast, the sticky floors of student kitchens and high ceiling’d Glasgow tenements crowded with bric-a-brac art experiments. Scuffed Doc Martins, the Glaswegian chokey brawl. Pale skins, no football colours. Pints of Tennants, £3 Dahl at the student union on white enamel plates, Sports Direct caps, feet hurting from walking up and down West End hills. Hiking trousers tucked into socks. Bargain charity shop finds, going to every supermarket on Sauchiehall Street. Straight to the reduced section to pick up that week’s tea. The teenage fear of not belonging but also the main character egotism of wanting to discover who you are and what you’re capable of.

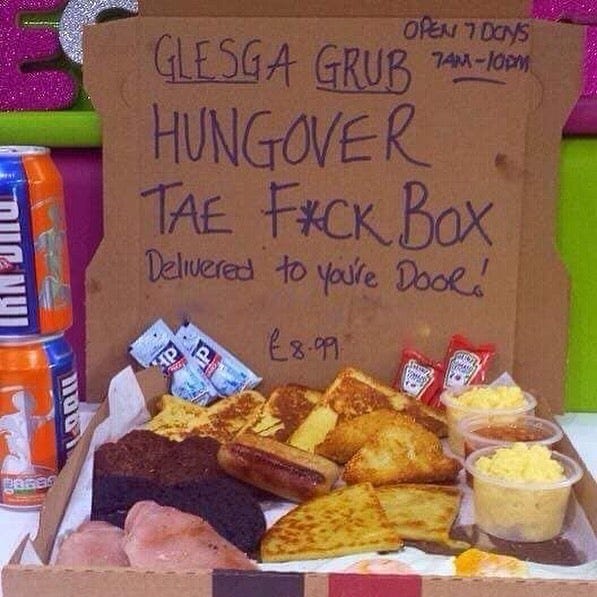

I go back every few years, was there just last week. The city has swelled with moneyed outsiders making Glasgow their home. With this, gradually, desires for new Ottolenghi-style eateries, nutty ground coffee beans, fluoro pink Barras stalls fresh with international imports instead of a twisted jumble of antiques and electronics. The Glasgow I knew had changed so much in 6 years. I wondered about my own part in this. How I’d come to the city with my own notions of what makes a place interesting. My own presence – my London accent (and attitude?) – infiltrating the locality. Is Glasgow to follow the same fate as London, where indie high streets are one by one sucked up by multi-conglomerates or the middle classes opening cute shops as a means of a bit of extra income.

“There is a dialogic relationship with culture – when consumers learn that uncomfortable = bad instead of expansive, they develop an equation of passivity with the art-going experience. In the end, the definition of what is “good” becomes what to not challenge, and the entire endeavour of art-making is undermined. Profit making institutions then become committed to producing what the Disney-funded design programs call “Imagineers”, the craftsman version of Mouseketeer’s, workers trained to churn out an acceptable product, while thinking of themselves as artists.” – SS.

To understand the history of areas we move in, its rich migration routes and the communities that have made that land their home, is a big ask. As a young person in Glasgow I did little to research the history of my neighbourhood and it took a few years to actively integrate myself in the population outside the student body. The same goes with my friends new to London. When they visit Bloomsbury, they see prim, clean and well looked after central London with some cute shops to wonder round. They don’t know the burning heat behind my eyes. The erasure of business owners where to be entrepreneurial wasn’t just about making money. Gut wrenching pain covered up with the click clack of new boots.

Shoshin-sha; beginner’s mind

“This new crew, the professionalised children of the suburbs, were different. They came not to join or blend in or to learn and evolve, but to homogenise. They brought the values of the gated community and a willingness to trade freedom for security. For example, neighbourhoods became defined as “good” because they were moving towards homogeneity. Or “safe” because they became dangerous to the original inhabitants. Fearful of other people who did not have the privileges that they enjoyed, gentrifiers–without awareness of what they were doing–sought a comfort in overpowering the natives, rather than becoming them.” – SS.