The Culture Regeneration Machine

In biological chemistry, Autopoiesis refers to a system capable of producing and maintaining itself by creating its own parts. Coined in the 1972 publication Autopoesis and Cognition: The Realisation of the Living, Chilean biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela define the self-maintaining chemistry of living cells. But I first came across the term via the essay In Subverting machines, fluctuating identities: Re-learning human categorization by Christina Lu, Jackie Kay and Kevin McKee. In the paper, the writers discuss the term against the context of machine learning, exploring the fantasy of AI as autopoietic; that the circular processes of input and output can perhaps one day be self-sustaining akin to the ever-mutating human condition.

“We apply our theory to sketch approaching autopoietic identity through multilevel optimisation and relational learning. While these ideas raise many open questions, we imagine the possibilities of machines that are capable of expressing human identity as a relationship perpetually in flux.”

While the AI theorists investigate the possibilities of technology, adopting Donna Haraway’s Cyberfeminist ontology imagining new identities that dissolve the boundary between human and machine, the concept of Autopoiesis stuck with me as a way of thinking about creativity. To be more accurate, the Western creative industry. Just as AI sustains the original dream of technology; of a boundless, democratic resolve imbued with frictionless ease and infinite scalability; the creative industries also once hoped to provide a similar utopia of wild imaginings. Albeit in a less immediate and more abstract way. By “creative industries”, I am specifically talking about the industries I work in, visual creativity bound to the agency-client model. Creativity encompassing the systems of art direction, creative ideation and all the various disciplines that are interspersed with these roles; photography, illustration, graphic design, advertising and so on.

Unknown engraver - Humani Victus Instrumenta - Ars Coquinaria

Ideally, the creative industries, and in turn the creative process, should be autopoietic; circular, absorbing a myriad of influences that enrich the thinking and output of any project at hand. This output then becomes democratic, inspiring new webs of culture, and the cycle continues.

"An autopoietic machine is a machine organized (defined as a unity) as a network of processes of production (transformation and destruction) of components which: (i) through their interactions and transformations continuously regenerate and realize the network of processes (relations) that produced them; and (ii) constitute it (the machine) as a concrete unity in space in which they (the components) exist by specifying the topological domain of its realization as such a network." - Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela, Autopoesis and Cognition: The Realisation of the Living

They describe the space as self-contained, happening in a space that “cannot be described by using dimensions that define another space”. For me, creativity should occur in a similar space; pulling from various fragments of history and speculative futures – politics, history, science, literature, technology and so on – to form unique strands of creativity expressed through an interdisciplinary, multi-layered experience. Creative expression is a projection of these various systems at play. Our biases and subjectivity manipulate the projections and thwart creativity to become inseparable from human perception; much like AI and how its outputs are bound to its human data sources.

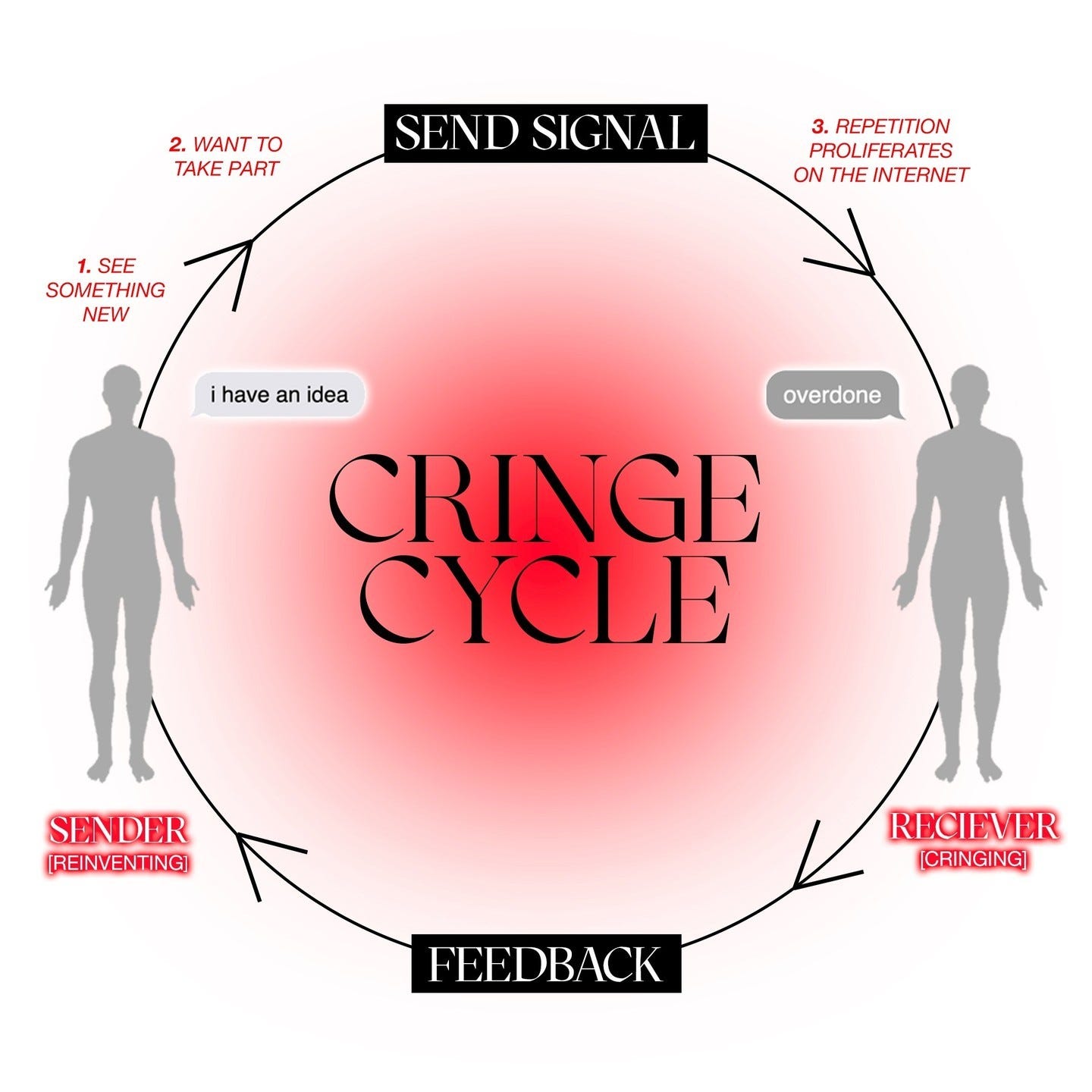

But when the creative process (and in turn industries) find itself in a loop – homogenous algorithms cough up the same references, styles, and schools of thought in a vacuum – this is when autopoiesis cannot take place. How can living cells self-maintain healthy biology when the balanced cycles are skewed to a singular data set. When the creative industries are dominated by white culture predicated on colonial, capitalist values; how can creativity regenerate in an all-encompassing way authentic to the variety of cultures at play. At present, so much of what comes out of the creative industry is homogenous and diluted for this reason, playing the same role in different guises and mimicking hype-driven references that saturate the industry, and in turn culture, with superficiality devoid of rigorous thought.

MØRNING FYI

“Why make art if you have nothing to say? And why make it you’re not going to respond to the world around you?” – Fariha Roisin.

In The Algorithmic Internet, Christina Lu discusses the dangers of GPT-4chan, how people can use it to cause harm as the human-machine feedback loop produces entropy, thus meaning its knowledge is incomplete. “It is dangerous because of the volume at which it could have said these things, the people it could have baited or inspired, the ease with which an infinite number of digital maws could have produced with its intentionless spew. Id ad nauseam. This is the forest that AI ethics researchers miss for the trees. While preoccupied with creating taxonomies of harm, we have neglected to scrutinize how these harms actually disseminate, perhaps taking that logic for granted. In the words of Gilbert Ryle, we require ‘knowing how’ beyond simply ‘knowing that’.”

I’d like to draw the parallel between what Christina is saying about AI but apply it to the creative industries. The creative industries have become so entrenched in capitalist doctrines; growth, financial gain, likes and shares, job titles, more labour, more emotional input, more, more, more; that creativity no longer becomes about saying something interesting in the world, but about creating a reaction in this sea of insidious doom scrolling. To put it even more bluntly, it becomes about what can secure your attention the longest, the now most valuable commodity being attention. To reiterate, in the words of Gilbert Ryle, creative industries need to reassess ‘knowing how’ beyond simply ‘knowing that’.

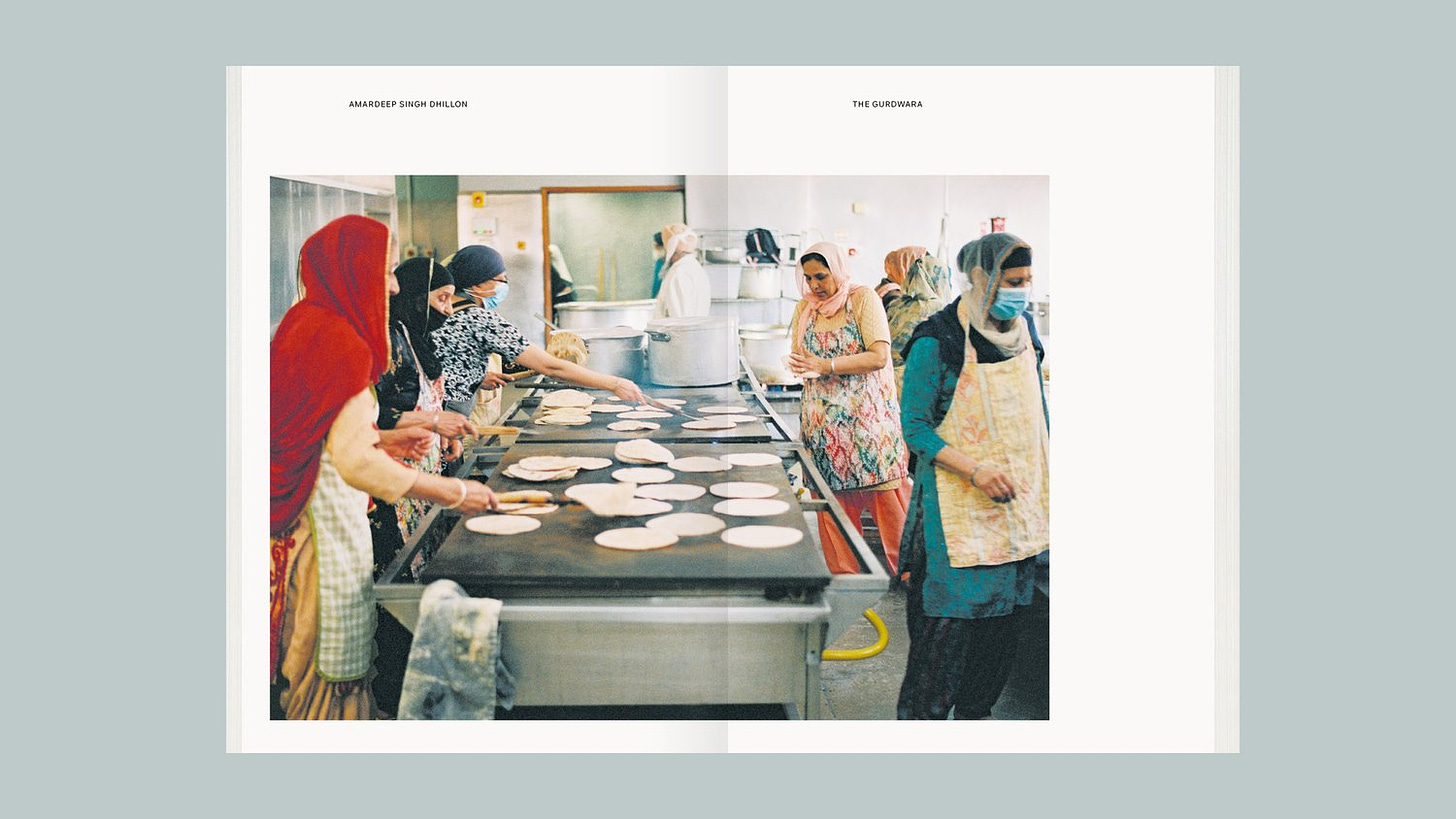

Jonathan Nunn: London Feeds Itself

In Jonathan Nunn’s London Feeds Itself, the writer and food critic celebrates the culinary culture happening in the margins. He is not interested in Michelin stars or trendy eateries designed for Claptonites or demographics of that ilk who choose to queue up for Dishoom or Dusty Knuckle for hours on end. Instead, he explores London’s culture through the food of the suburbs. “It’s true to say that London is now a city without a cultural centre; it is polyvalent, with multiple centres located in ever-expanding concentric circles emanating out from its geographic centre point. What was once the centre is being pushed out to the peripheries.” His argument being that the centre of London has similarly become victim to the soulless corporate sterility that comes with a Pret and Five Guys on every corner. “In an inversion of Paris (where Paris is always the arrondissements, and everything out of the arrondissements is not-Paris, what is in the London suburbs increasingly feels more like London than what is in its centre.”

As someone who grew up in Stoke Newington and then pushed out to Cricklewood, I have seen this in real time. Where the Pho mile used to cater to its local immigrant communities, now its restaurants are crowded with young Hackneyites, whereas Collindale and Barnet are the new hubs for immigrant communities. The book celebrates these culinary communities that exist in areas like Hounslow, Wembley, New Malden, Limehouse. And in this way, I understand London as a city to be autopoietic. Though the geographical location of its cultural hubs disperse further and further away from Whitehall, London continues to regenerate and culturally thrive through the one thing that makes it such an interesting, rich place to live in; immigration and the mixing of cultures.

Growing up, to get creative inspiration, my main go-to was art galleries. I wondered through the Tate and Royal Academy to stare at paintings on the wall and scrutinise captions describing life hundreds of years ago. Nowadays, I don’t need to go to galleries to soak up such inspiration. I can feel it living on the streets, storefronts and within the communities that aren’t bound to, or limited by, hype cycles. Places that embody the fragility and uncertainty of life. Terrifying but also exhilirating and beautiful because it is in the moment, ephemeral.

Jonathan Nunn: London Feeds Itself

London has many many things wrong with it; centralised funding probably being one of its biggest. But there is also so much to love about the city. So much that goes overlooked or taken for granted amongst the rat race. “To write about the city with love is to be in a constant state of grief for the places we lost to time,” writes Jonathan. He lists the Elephant and Castle bingo hall, the arepa stand that became a Sports Direct, and a Kurdish community centre that became a Beyond Retro. For me, it’s the now closed down dishevelled jazz bar on Church Street, the old pizzeria in the old Brunswick Centre, the Aunty-owned tau fu fah coffee shop on Lisle Street.

While there is grief, there is also much to celebrate in the present. Jonathan writes, “The best spaces seem to exist outside time itself, defying the financialisation of time that measures out leisure in thimble-sized portions… spaces that constantly regenerate to house new flow, new communities – sticking points, as writer Rebecca May Johnson calls them – in the endless river of capital that courses through the city. It is not a surprise that all these spaces are, in their own ways, precarious, besieged by time and in constant need of protection.”

By learning from urban movement and technology, perhaps the creative industries can move towards a more holistic regeneration cycle. If only the creative industries could be like London, “feeding itself”.

“Velocity is, if you recall from school, space over time plus direction, and all these essays are really about London’s velocity. Everything in London is expanding outwards and upwards at a space that seems almost unstoppable. London is eating itself, but this is neither irreversible or inevitable. Italo Calvino warned us about cities being ‘the inferno of the living’ in his 1972 book Invisible Cities. London is a city as infernal as any other, but Calvino also gave us the cheat codes: to ‘seek and learn and recognise who and what, in the midst of the inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space’. London is feeding itself too.”